March On Washington, 28 August 1963

March On Washington

The March On Washington for jobs and freedom was a turning point in the Civil Rights Movement. Dr. Martin Luther King emerged as the star, but we must always honor A. Phillip Randolph and Bayard Rustin for organizing this incredible event, which amplified global support for the Civil Rights Movement.

Many young people think the March On Washington for Jobs and Freedom was planned as a showcase for southern civil rights leaders like Dr. Martin Luther King. Not true. In fact, the 28 August 1963 civil rights event wasn’t even the first planned March on Washington.

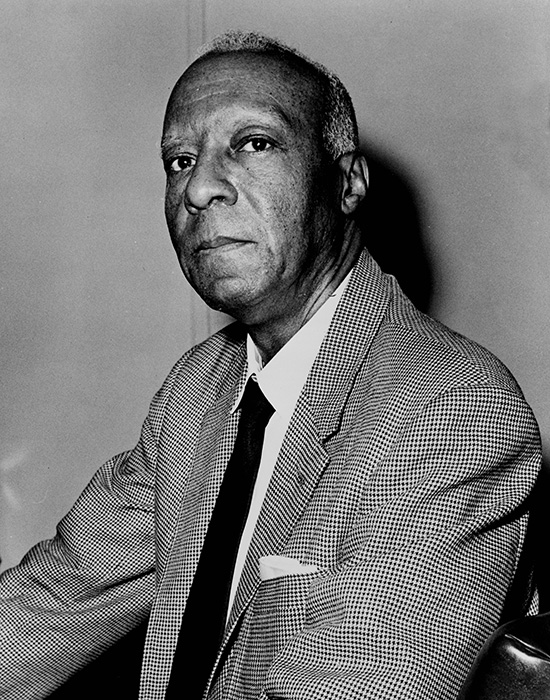

In 1941, Asa Phillip Randolph, President of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Vice-President of the AFL-CIO, planned the first March on Washington to make demands for access to military and federal jobs and social freedoms. For context, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was the most powerful black labor organization in America who could affect railroad service nationwide, when passenger service in overnight sleeping cars dominated long distance travel. The timing of such a march would embarrass America’s federal government and military leaders, eliminating their ability to proclaim a moral high ground for our soldiers versus Hitler in Germany and Tojo in Japan.

Towards that goal in 1941, Randolph, Walter White (NAACP), and T. Arnold Hill (National Urban League), met with President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Congressional leaders several times to press for federal jobs and social freedoms. Roosevelt persuaded Randolph call off the March for Access to Defense Jobs to prevent civil rights leaders being labeled “unpatriotic” as America was nearing entry to World War II. Randolph was severely criticized by Bayard Rustin, among others.

A. Philip Randolph in 1963

But in return, Randolph convinced Roosevelt to issue a 3-part Executive Order that African-Americans be admitted into job training programs in defense plants, forbade discrimination by defense contractors, and established a Fair Employment Practices Commission. That is why we can celebrate Randolph’s “Threatened” march opening roughly a million jobs to African-Americans during the war. Randolph also demanded that the U.S. military be integrated. President Roosevelt would not yield to his last demand until he saw how black soldiers performed in the war.

Roosevelt’s final position was communicated by Randolph, White and Hill to the masses. It emboldened black soldiers to bravely fight during World War II — for the victory over German and Japanese forces abroad, and a victory over discrimination at home. Optimistic black soldiers thought that government, military and public facility discrimination would not outlive another war. When President Roosevelt suddenly died in office on 12 April 1945, just months before war ended, Vice-President Truman assumed the presidency.

In summer 1945, black soldiers returned home to public facilities, transportation and restaurants just as segregated as in summer 1941. Words can not describe their degree of emotional letdown. These harsh facts were amplified for African-American government workers, who believed that our nation’s capitol would set a national example of social freedom and progress just as the war ended. It was also a tremendous letdown to defense plant workers around the nation, who anticipated a Executive Order that would immediately desegregate the military and open even more federal jobs. That would have been a powerful federal leadership signal to governors to do the same for state jobs.

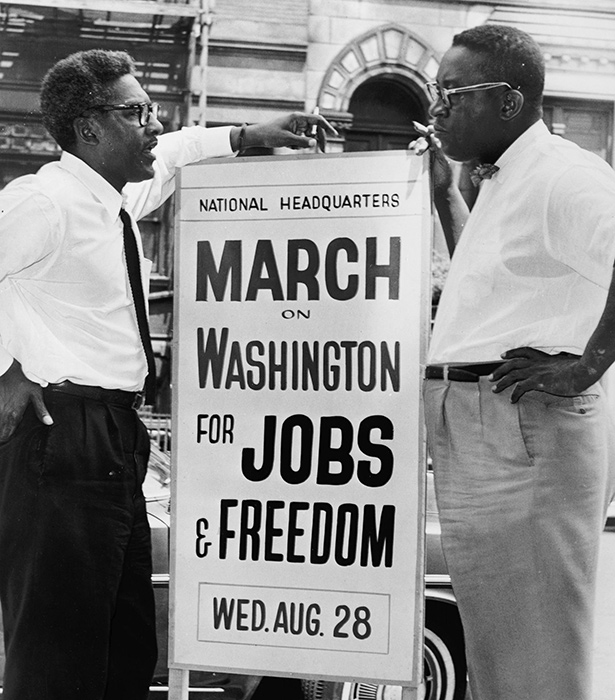

Bayard Rustin & Clifford Robinson

Neither President Truman or Congress shared a sense of commitment to take further immediate civil rights measures, as promised to Randolph and others. After three more years of threats of a march and further negotiations, Randolph and others finally convinced President Truman to desegregate the Armed Forces in 1948. Thus, one can credit A. Phillip Randolph as the Father of Modern American Civil Rights Movement.

Randolph was also a friend and supporter of Mary Church Terrell. In 1953, Terrell launched the District of Columbia vs. John R. Thompson case that led to the U.S. Supreme court to outlaw discrimination in public restaurants. Even tax-paying, property-owning Black citizens could not dine any where in Washington, nor vote in most Southern states. Her Legal Case, followed by the Brown vs. Board of Education Case decided by the Supreme Court outlawed “Separate, But Equal” in 1954. Those legal precedents made Washington DC the focal point of the Civil Rights Movement from 1941-55.

Momentum to accelerate progress was building. Though President Dwight Eisenhower got a wimpy 1957 Civil Rights Bill passed in 1957, On 11 June 1963, President John F. Kennedy became the first president to submit a major Civil Rights Proposal to Congress. Democrats controlled Congress, but Southern Democrats (“Dixiecrats”) stalled it, even as the most shameful events of white racism were nationally televised from Alabama and Mississippi. That gave hope to the march organizers and participants. Sadly that night, another Civil Rights leader, Medgar Evers, was assassinated in Jackson, Mississippi.

But hope is not easily killed. Plans for the march went on.

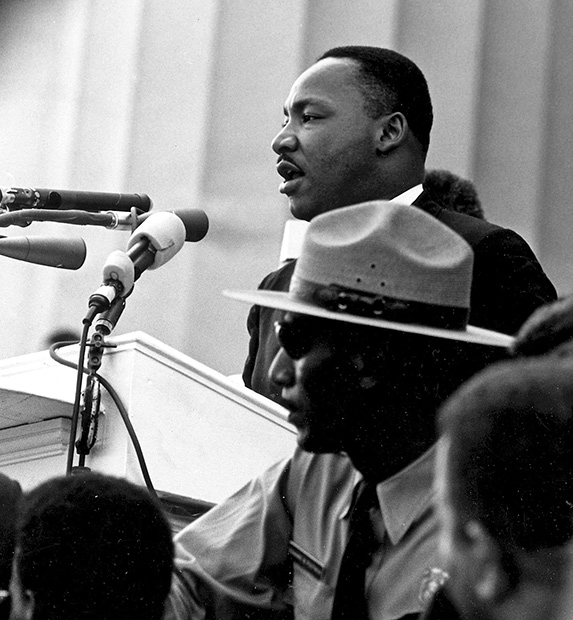

Dr. Martin Luther King giving his I Have A Dream speech

The 28 August 1963 Civil Rights March on Washington made it clear to the world that 250,000 Negroes came to proclaim their rights in the so-called American democracy. The march was about more than Civil Rights and the timing was right. Few Black citizens could get federal jobs, even when overqualified. With the labor union backed A. Phillip Randolph and Bayard Rustin involved, jobs had to be addressed at the podium. Bayard was the principal organizer who can claim the lion’s share for the event going off so smoothly that there was not one reported act of violence. When you watch a video of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. giving the speech, notice how many folks surrounding him have their labor union caps on. That speaks directly to the labor connections of Randolph.

When Randolph and Rustin presented their 1963 March On Washington plan to JFK, they did it to receive his public support, not his blessing. JFK nervously gave his support because no one had organized a march that big in Washington. Randolph and Rustin reassured him of their organizational prowess and moved forward on 28 August 1963. The rest is history.

Afterwards JFK welcomed the march organizers to the White House. Beaming like a proud father congratulated them for a well run event and memorable speeches, particularly Dr. King’s I Have A Dream, that would help him advance Civil Rights legislation. Though Dixiecrats and other sympathizers in Congress would continue to block legislation, JFK and his brother the Attorney General Robert Kennedy, helped by cracking down on KKK violence and offering federal troops for Freedom Riders who desegregated interstate transportation and more lunch counters.

March On Washington leaders at the Lincoln Memorial

Though JFK’s was assassinated on 22 November 1963, President Lyndon Johnson leveraged its halo effect, his Southern political muscle and choosing states where federal contracts would be awarded to get Civil Rights legislation enacted. Simultaneously, Randolph, Rustin, Dr. King, John Lewis and many other civil rights leaders kept bending his ear to sign the Civil Rights Act in 1964, Voting Rights Act in 1965 and Fair Housing Act of 1968. In his Great Society Program, President Johnson planned to implement job programs similar to those proposed by Randolph and Rustin. But the Vietnam War robbed the U.S. Treasury of being able to properly fund the program.