Katherine Dunham

Katherine Dunham

Who is Katherine Dunham? Dancer, choreographer and teacher are the most common answers. Others say activist and anthropologist, artist and author. Some hail her as a scholar and icon of stage and screen. Still others say pioneer, hero and warrior. One will even hear Dunham described as a Voodoo priestess. Oprah Winfrey, unarguably the most influential woman in American media today, declared Dunham a legend. Dance historians salute her as the “Queen Mother of Black Dance.” Jean-Bertrand Aristide, the first democratically elected president of Haiti, proclaimed her the “Spiritual Mother of Haiti.” To her only child Marie-Christine, Katherine Dunham was simply “Mother.”

The truth is, Katherine Dunham is all the above and more. Throughout 2009—the centennial year of her birth—the Missouri History Museum in St. Louis offers a major museum exhibition, Katherine Dunham: Beyond the Dance, to celebrate the many facets of the Renaissance woman known as “La Grande Katherine.” The exhibition sweeps aside the boundaries between theatre and museum as the visitor explores her contributions to dance and anthropology. Her career spanned decades and continents, as well as her activism. Since debuting in 2008, Katherine Dunham: Beyond the Dance has garnered overwhelmingly positive response.

Katherine Dunham’s father was an African-American businessman in Chicago. Her mother was a French Canadian schoolteacher. Although Dunham sang in her local Methodist Church in Joliet, IL, she became fascinated with dance from a young age. At age eight, she both amazed and scandalized the church elders by doing a performance of non-religious songs at a cabaret party, in order to raise money. Before finishing high school, she started a private dance school for young black children. Given limited life choices for Black women in that day, Katherine consented to her family’s wish to become a teacher and followed her brother, Albert Dunham Jr., where she became one of the first African American women to attend the University of Chicago, and she earned bachelor, masters and doctoral degrees in Anthropology.

Following graduation, Dunham founded the Negro Dance Group who performed at the Chicago Beaux Arts Theater in A Negro Rhapsody, and danced with the Chicago Opera Company. One of the performances was attended by Mrs. Alfred Rosenwald Stern, who arranged an invitation for Dunham to appear before the Rosenwald Foundation, which offered to finance any study contributing toward her dance career that she cared to name. Hence, Dunham spent the next two years in the Caribbean studying all aspects of dance and the motivations behind dance. Haitian dance held a special resonance for her, as she wrote in essays during her trip.

By the 1930’s, she transformed Black dance them into significant artistic choreography that speaks to all and developed an idiom to speak about it in a professional and scholarly manner. Thus, she was one of the founders of the anthropological dance movement who showed the world that African American heritage is beautiful and that Caribbean and Brazilian dance anthropology were richly deserving as a new academic discipline.

In 1931, Miss Dunham met one of America’s most highly regarded theatrical designers, John Pratt, forming a powerful personal and creative team that married in 1949 and lasted until his death in the 1986.

In 1944 she opened her first school in NYC, followed in 1945, when she opened the famous Dunham School at 220 West 43rd Street in NYC, where artists such as Marlon Brando and James Dean took classes under her tutelage and influence before the Civil Rights Movement. She then founded the Katherine Dunham Dance group, which developed into the famous Katherine Dunham Company devoted to African-American and Afro-Caribbean dance. Miss Dunham also worked as a director in the Federal Theater Project. She co-directed and danced in Carib Song at the Adelphi Theater in New York in 1945, and was producer, director, and star of Bal Nègre at the Belasco Theater in New York in 1946.

Word of this gifted multi-talented lady got around, so Katherine Dunham appeared in several movies, including: Carnaval of Rhythms (1939), Star Spangled Rhythm (1942), Stormy Weather (1943), Casbah (1948), Botta e Risposta (1950 Italy), Musica en la Noche (1955 Mexico), Liebes Sender (1954 Germany), Mambo (1954 Italy), and Karaibishe Rythmen (1960 Vienna). She also choreographed, without appearing in: Pardon my Sarong, (1942), Green Mansion (1958), and The Bible (1964). Dunham choreographed Aida in 1963, becoming the first African American to choreograph for the Metropolitan Opera. The Katherine Dunham Company last performed was in 1965 at the Apollo theatre.

Katherine Dunham wrote several revealing books about her experiences and an autobiography of her childhood. Dunham was always a formidable advocate for racial equality, refusing to perform at segregated venues in the United States and highlighted the irrationality and embarrassment of American discrimination to people in high places worldwide. The latter was an important external pressure to help defeat discrimination.

Whenever engaged in conversation, she used the opportunity to teach and strategize to solve the social problems created by poverty and racism. She even re-directed the energy of some violent street gang members through the performing arts. Miss Dunham’s efforts continue at her centers in greater St. Louis. Speaking of her activist side, in 1992, at age 82, Dunham went on a highly publicized 47-day hunger strike to protest against discriminatory U.S. foreign policy against Haitian boat people. In 2002, Molefi Asante gave Katherine Dunham well-earned inclusion on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

Today, the Dunham Technique—in which the dancer incorporates traditional African and Caribbean dance with techniques of classical ballet and modern dance—is a part of the standard training for modern dancers. Thus, Dunham is considered one of the great dance pioneers of the 20th century alongside Isadora Duncan, Martha Graham and Alvin Ailey. During her robust career, she choreographed more than 90 individual dances – enough to 3 or 4 careers.

Although Dunham died on 21 May 21 2006, just weeks before her 97th birthday, her contributions to dance, civil rights and the St. Louis region remain a marvelous legacy for all to enjoy.

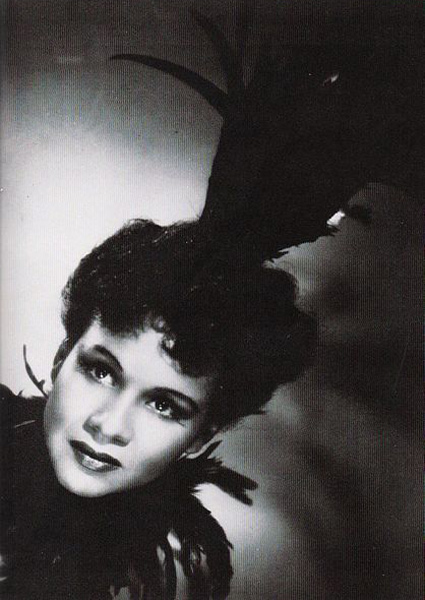

A stunning portrait of Dunham from 1943 greets visitors upon their entrance to Katherine Dunham: Beyond the Dance. The painting by Werner Philip captures Dunham in a reflective, quiet moment. This is one of the few times when the visitor will see the young Dunham at rest. Other images in the exhibition show Dunham in constant motion as she dances, teaches and battles injustice. The exhibition is divided into four categories. A biography section introduces the visitor to the Illinois-born girl who would grow up to be an international dance star. The other three sections each represent the geo-cultural influences from which Dunham drew inspiration: Afro-Caribbean, African and American.

Enlarged photographs, colorful costumes, props and video vividly bring to life dance performances that were inspired by each of the three cultures. Among these performances are Haitian Roadside, which featured native songs such as Chocounne sung by Dunham herself; Afrique, which Dunham dedicated to the country of Ghana; and Scott Joplin’s opera Treemonisha, which Dunham choreographed in the 1970s.

The centerpiece of the exhibition is the recreation of the stage for Rites de Passage, an epic dance production, which chronicles the journey of life: Puberty, Fertility, Death and Women’s Mysteries. It is an extraordinary example of the work of theatrical designer and husband John Pratt.

Other highlights of the exhibition include personal items belonging to Dunham: masks used in ceremonies and sacred rituals from around the globe; scrapbooks chronicling Dunham’s career, global travels and significant events in world of dance and her artwork collection. Dunham donated a substantial portion of her personal and professional items to the Missouri History Museum in 1991. Two other significant repositories of Dunham artifacts are the Dunham Dynamic Museum in East St. Louis, IL and Southern Illinois University in Edwardsville.