Black Hollywood History – 1

Black Hollywood History started when movies started screening across America in 1896 shortly after the Supreme Court sanctioned racism in the Separate, But Equal ruling. Movies were the principal medium to communicate news, social customs, and visual entertainment to millions of Americans each week. Thus, Hollywood movies, more than school books and bibles, shaped white folks’ perceptions of black folks.

In 1905, most African-Americans portrayed in Hollywood films were white actors in blackface. To summarize writer Gary Null in his book Black Hollywood, movie studios adopted a long-standing, minstrel stage practice of portraying black males as slow-talking, slew-footed, irresponsible dim-wits, and lazy bucks. This movie practice even appeared in children’s animated films and continued up through December 1941 before the start of World War II. Hollywood studios finally realized it was insulting and bad salesmanship to defy complaints by the NAACP and A. Philip Randolph when African Americans were needed for weapons manufacturing and storage during World War II.

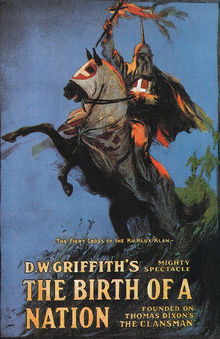

The most damaging perception of the black male image was manufactured in the 1915 movie Birth of a Nation. Studio mogul D.W. Griffith spared no expense producing and directing Hollywood’s first epic movie — a glorified Klu Klux Klan recruitment film.

The most damaging perception of the black male image was manufactured in the 1915 movie Birth of a Nation. Studio mogul D.W. Griffith spared no expense producing and directing Hollywood’s first epic movie — a glorified Klu Klux Klan recruitment film.

Birth of a Nation advanced the art & science of filmmaking and did box office sales equivalent to 1997’s Titanic movie.

White audiences too young to witness the Reconstruction Era (1865-1877) cheered with each repeated viewing of its spectacle. As powerful propaganda, the movie enabled 20th-century white folks to emotionally connect with white southerners who resented black citizenship after the Civil War. Black male stereotypes were bronzed in Birth of a Nation: untrustworthy, savage, dumb, slow, bug-eyes, murderer, and worst of all, rapist of white women. To slightly re-write a phrase coined about the film, “It was like re-writing history with lightening.”

Based strictly on criteria that ignore racial propaganda and historical truth, Birth of a Nation was an artistic milestone of cinema. But in the 21st century, should a milestone of artistry and epic scale be the only criteria to keep it on the American Film Institute 100 Greatest American Films List? If so, then Spike Lee’s Malcolm X must belong on the AFI list as well.

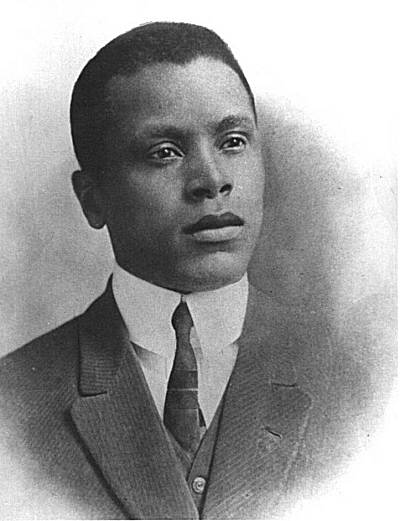

For overcoming obstacles Black Hollywood History that permitted little room for self-confident black entrepreneurs, we are forever indebted to Oscar Micheaux for creating Black Roadshow Cinema.

Oscar Micheaux

In the absence of a strong black movie studio, most professional black actors in the 1920s-40s earned a living in a limited number of Broadway roles or elbowed for nanny or butler roles in Hollywood. Furthermore, movie trade unions were closed to African Americans who aspired to craftwork behind the lens as writers, directors, cinematographers, editors, set designers, costumers, carpenters, plumbers, painters, make-up, and hairstylists.

Another horrible legacy was visited upon an infant Black Hollywood. In 1925, Stepin Fetchit (Lincoln Theodore Monroe Andrew Perry) arrived. Beginning in 1925, he played in 51 movies, became a Hollywood star to white fans, and a millionaire during the Great Depression. Unfortunately, his ingratiating acting persona was the perfect metaphor to slander one race of people for the entertainment of another.

Viewing his need for work in the most charitable light, one can understand him playing a dim-witted, bug-eyed flunky to acquire a pile of money otherwise out of reach to African Americans. But by the mid-1930s, the NAACP and black newspapers’ criticism of his roles expanded to a roar. I don’t know how long his studio contract lasted, but by 1938, he had enough money for the rest of his life. If he chose to work, Mr. Perry could have left for Broadway, as many other black actors did. But Stepin Fetchit stayed to play variations of the same demeaning caricature until 1953. That equates to selling his soul for a dollar.

To movie studio executives, Stepin Fetchit created a bankable role to spin-off and repeat with other actors. Raised with racial stereotypes and blinded with greed, they only imagined African Americans in servant, dim-wit, or musical roles. In the latter cases, black musicians, dancers, and singers, including Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and Paul Robeson, were recruited to deliver that “natural rhythm.” Fortunately, after years of NAACP protest and notable black actors turning down work in Hollywood, a touch of dignity snuck in the back door.

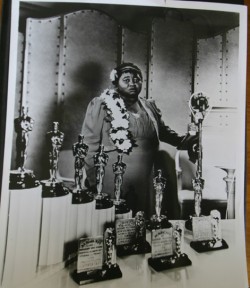

Hattie McDaniel wins Best Supporting Actress for Gone With The Wind

With the notable exceptions of Ethel Waters, Lena Horne and Hazel Scott as leading ladies in a few movies, talented black actors like Hattie could not find professionally satisfying work in Hollywood.

By the late 1940s however, enough black actors and musicians were gainfully employed in Hollywood to form a Sugar Hill residential district surrounded by Washington Blvd, Western Avenue, Adams Blvd, and Normandie Avenue in the West Adams District. A summary of this era can be read in Thomas Cripps’ book Making Movies Black.

An inkling of social progress was afoot in Hollywood after World War II. In 1950, Hazel Scott hosted a national network TV show. Unfortunately, the brief-lived show never attracted many stars or sponsor support.

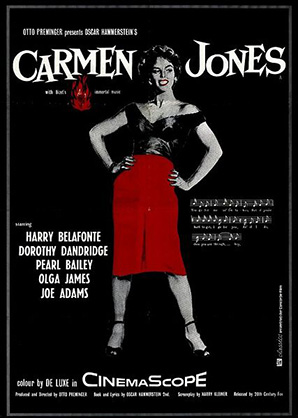

James Snead’s book White Screens, Black Images provides a penetrating look at the 1950s when several Black actors established leading roles. Dorothy Dandridge, a successful national nightclub singer and bit-role actor from the 1940s through 1953, led the charge. When Dorothy heard that an all-black production of Carmen Jones was planned for 1954, she embraced it with both arms. Based on her earlier roles, Austrian director Otto Preminger had a dainty image of Dorothy and initially cast her as the meek girlfriend of Harry Belafonte. But Dorothy, dressed as Carmen Jones, entered Otto’s office and seduced him into awarding her the sultry role of a lifetime. Prior to the film’s release, Dorothy also appeared on the November 1st cover of Life magazine. Thus, media buzz built up for Dorothy Dandridge as Carmen Jones, to become the first African-American to be nominated for Best Actress.

Dorothy Dandridge had the same magnetic beauty and acting verve as her white contemporaries Marilyn Monroe, Ava Gardner and Elizabeth Taylor. Unlike them, Dorothy could also sing and dance, so Carmen Jones should have been the breakthrough role and Best Actress Nomination that opened more doors. She forgot that black actors had NO latitude for career mistakes.

Dorothy Dandridge had the same magnetic beauty and acting verve as her white contemporaries Marilyn Monroe, Ava Gardner and Elizabeth Taylor. Unlike them, Dorothy could also sing and dance, so Carmen Jones should have been the breakthrough role and Best Actress Nomination that opened more doors. She forgot that black actors had NO latitude for career mistakes.

A studio executive asked that Dorothy play something unthinkable for white Best Actress Nominee — slave character in a minor role AFTER her nomination in the film The King and I. Dorothy verbally agreed with the studio chief to play the role just before learning of her Carmen Jones Oscar nomination. The studio chief informed his production team, board of directors, and other studio chiefs that he hit a home-run by casting Dorothy Dandridge in the upcoming role and therefore, put his reputation on the line.

Carmen Jones was an all-black movie amenable to white audiences. To increase her box-office appeal in subsequent white-dominant movies that decade, the studio chef wanted to gradually increase Dorothy’s acceptance with white audiences.

Understanding race relations in 1955, Dorothy should have negotiated a Supporting Actress-level presence for the Tuptim role to set the stage for advancing roles in subsequent A movies. In that way, she could persuade the studio boss to make more money on a “Black Star with Crossover Appeal” in the long run.

Unfortunately, Dorothy listened to her director-lover Otto Preminger and reneged on the Tuptim role eventually played by Rita Moreno. Dorothy committed the ultimate sin for any actor during the Studio System — breaking a verbal or written contract with a studio chief. In that system, powerful studio chiefs decided which actors would be hired, loaned to other studios, demoted to B movies, and blackballed from work. Only established money-makers like Humphrey Bogart, Betty Grable, James Stewart, John Wayne, Marilyn Monroe, Gary Cooper, and Burt Lancaster could buck the studio system in 1955.

Dorothy could take solace from Carmen Jones that permitted her to buy a beautiful home in the Hollywood Hills. But she was demoted to the 1957 Island In the Sun movie, where neither she nor Harry Belafonte could kiss their interracial lovers. Afterward, Dorothy was blackballed.

Future acting roles for the lady that Lena Horne called, “Our Marilyn Monroe”, would be few and far between.

Despite Dorothy Dandridge’s horrible experience, Hollywood was progressing on social issues faster than the rest of America. One milestone happened in November 1956 when the Nat King Cole Show launched on NBC TV broadcast nationwide. Begun as a 15-minute live show, it expanded to 30 minutes in July 1957. And for good reason. Unlike the earlier effort by Hazel Scott, Nat’s show had star power: Ella Fitzgerald, Harry Belafonte, Frankie Laine, Mel Tormé, Billy Preston, Eartha Kitt, and other stars worked at scale to support the fledgling program. Despite attracting a modest national audience, Nat King Cole Show could not obtain a major national sponsor. Without national sponsorship, the last episode aired on 17 December 1957.

Undaunted, Nat played in short films, sitcoms, television programs, and several big-budget movies where he secured legions of adoring fans of all races. Today’s Hollywood stars can also thank Nat King Cole for crossing the residential color line in the late 1950s when he purchased a home in the Hancock Park district of Los Angeles. For those who don’t know, old-money Hancock Park is located south of Hollywood. It has many homes equivalent to Beverly Hills. In the 1950s, it had many movie stars too.

Dorothy Dandridge’s career troubles were shown in full display in her next movie role, 1957’s Island In The Sun. She and Harry Belafonte acted in a story of two interracial relationships on a Caribbean island. It was a hot concept, but studio executives feared that interracial relationships on screen would damage box office appeal to white audiences. Consequently, they would not along the actors to kiss, hug or engage in racy dialogue.

Dorothy Dandridge’s career troubles were shown in full display in her next movie role, 1957’s Island In The Sun. She and Harry Belafonte acted in a story of two interracial relationships on a Caribbean island. It was a hot concept, but studio executives feared that interracial relationships on screen would damage box office appeal to white audiences. Consequently, they would not along the actors to kiss, hug or engage in racy dialogue.

Those artistic restrictions crippled the movie with incomplete character motivations. Critics justifiably panned it and patrons stayed away, which damaged Dorothy’s and Harry’s careers more than it did their white co-stars.

Dorothy’s next project was an Italian-French B movie in 1958 called Tamango. Ironically, money problems forced Dorothy to play slave-mistress in Tamango. Due to interracial love scenes between Dorothy and the white actor, Tamango was not released in America until 1962. The 4-year delay damaged her box-office appeal and B movie quality didn’t help either. She appeared in another B movie with James Mason later in 1958 titled The Decks Ran Red.

In 1959, studio executives called Harry Belafonte and Dorothy Dandridge to play lead roles in the cinematic adaptation of George Gershwin’s Black musical, Porgy and Bess. Belafonte was unwilling to play the demeaning role of Porgy. He urged Dorothy to do likewise. But Dorothy needed the money for her sick child and hoped that co-leading another A movie would end her blackball. Under similar threat of studio blackballing, Sidney Poitier played Porgy. Sammy Davis Jr. played his sidekick Sportin’ Life. Pearl Bailey played Maria and Diahann Carroll played Clara.

The film turned off African Americans and Southern Whites for mediocre box office. At least Dorothy’s performance earned a Golden Globe nomination for Best Actress. And in 1959, she married a white nightclub owner who happened to be another low-life character.

Though she remained vivacious, Dorothy Dandridge could only obtain roles in two C movies, Malaga (1960) and The Murder Men (1961) for the rest of her life. After losing money in her husband’s failing business and the divorce that followed in 1962, she sold her house to pay back taxes. Shrouded under a disintegrating career, loss of her child to a state institution, broken marriages, and financial losses, alcohol, and barbiturates became her closest friends.

Tragically, Dorothy died at age 41 from an accidental barbiturate overdose on 8 September 1965 in a Hollywood apartment. Was it really the price of being a defiant Black Hollywood pioneer?

1 2 3 Progress Sidney Poitier Tribute

Excellent research as inspirational as ever please keep me informed on innovators of Black cinema…..

Thank you….