Egypt History

The area encompassing Egypt was inhabited by 5000 BC, few written artifacts have been found from that Predynastic Period, which encompassed at least 2,000 years of gradual development of the Egyptian civilization. Around 3400 BC, two separate kingdoms were established near the Nile River Delta extending north to the Mediterranean Sea and south towards Nubia, today called Sudan. The Red Land to the north and the White Land to the south.

For the chronology of the Egyptian dynasties and pharoahs that followed, visit this weblink.

A southern king, the Scorpion, made the first attempts to conquer the northern kingdom around 3200 BC. A century later, King Menes subdued the north and unified Egypt, thereby launching the Early Dynastic Period (3100-2686 BC). King Menes founded the capital of ancient Egypt at White Walls (later known as Memphis), in the north, near the apex of the Nile River delta. Memphis grew into a great metropolis that dominated Egyptian society.

Most ancient Egyptians were farmers living in small villages, and agriculture (largely wheat and barley) formed the economic base of the Egyptian state. The annual flooding of the great Nile River provided the necessary irrigation and fertilization each year; farmers sowed the wheat after the flooding receded and harvested it before the season of high temperatures and drought returned.

The region today known as Cairo Metro Area, has been central to Ancient Egypt due to its junction of the Nile Valley (Upper Egypt) and the Nile Delta (Lower Egypt) that empties into the Mediterranean Sea.

Old Kingdom: Pyramid Builders (2686-2181 BC)

The Old Kingdom began with the 3rd dynasty of pharaohs. Around 2630 BC, the third dynasty’s King Djoser asked Imhotep, an architect, priest, and healer, to design a funerary monument for him. The result was the world’s first major stone building, the Step-Pyramid at Saqqara, near the city of Memphis. That city was also a crossroad between North Africa and the Middle East.

Egyptian pyramid-building reached its zenith with the Great Pyramid at Giza for Pharoah Khufu, who ruled from 2589 to 2566 BC. It remains the tallest Pyramid in the Ancient World. The ancient Greek historian Herodotus estimated that it took 100,000 men 20 years to build it.

Two other pyramids were built at Giza for Khufu’s successors Khafra (2558-2532 BC) and Menkaura (2532-2503 BC).

Riding camels to Giza pyramid complex; credit Murat Sahin

During the 3rd and 4th dynasties, Egyptian pharaohs conducted successful military campaigns in Nubia (“Sudan”) and Libya that added to their economic prosperity. The pharaohs held absolute power, provided a stable government, and faced no serious threats from abroad.

Over the 5th and 6th dynasties, the kingdom’s wealth was gradually depleted, partially due to the huge expense of pyramid-building. The growing influence of the priesthood around the sun-god Ra also diminished a pharaoh’s power. After the death of the 6th dynasty’s King Pepy II, who ruled for 94 years, the Old Kingdom period ended in chaos.

First Intermediate Period (2181-2055 BC)

The 7th and 8th dynasties consisted of a rapid succession of Memphis-based rulers until about 2160 BC, when central authority collapsed, leading to civil war between provincial governors. This chaotic situation was intensified by Arabian Bedouin invasions and accompanied by famine and disease.

From this era of conflict emerged two different kingdoms in the 9th and 10th dynasties based in Heracleopolis who ruled Middle Egypt between Memphis and Thebes, while another family of rulers arose in Thebes.

Around 2055 BC, the Theban prince Mentuhotep managed to topple Heracleopolis and reunited Egypt, beginning the 11th dynasty and ending the First Intermediate Period.

Middle Kingdom: 12th Dynasty (2055-1786 BC)

After Mentuhotep IV was assassinated, the throne passed to his chief minister, who became King Amenemhet I, founder of the 12th dynasty. A new capital was established at It-towy, south of Memphis, while Thebes remained a great religious center. Egypt flourished again. The 12th dynasty kings ensured smooth successions by making each successor co-regent which reduced jealousy for power.

Middle-Kingdom pharaohs colonized Nubia for its rich supply of resources (gold, ebony, ivory, etc.) and they repelled the Bedouins. The kingdom built diplomatic and trade relations with Syria and Palestine and military fortresses. They also mined quarries, enabling a return to pyramid-building.

The Middle Kingdom reached its peak under Amenemhet III (1842-1797 BC) and began its decline began under Amenenhet IV (1798-1790 BC) and continued under his sister and regent, Queen Sobekneferu (1789-1786 BC), who was the first confirmed female ruler of Egypt and the last ruler of the 12th dynasty.

Second Intermediate Period (1786-1567 BC)

During the 13th dynasty, Egypt was divided into several spheres of influence. The seat of government relocated to Thebes, while a rival dynasty (which became the 14th dynasty), settled in the city of Xois in the Nile Delta.

Around 1650 BC, a line of foreign rulers known as the Hyksos took advantage of Egypt’s instability to gain partial control of the kingdom. The Hyksos rulers of the 15th dynasty continued many Egyptian traditions in government and culture. They ruled concurrently with the line of native Theban rulers of the 16th and 17th dynasties, who controlled southern Egypt despite having to pay taxes to the Hyksos.

The Thebans launched a war against the Hyksos around 1570 BC, driving them out of Egypt.

New Kingdom (1567-1085 BC)

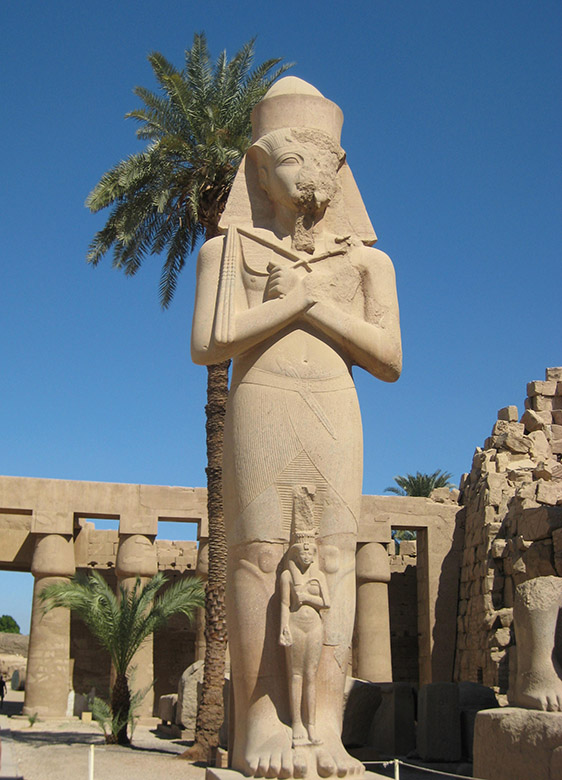

High Priest Amun with wife Mutemhat (small) at Karnak Temple, Luxor; credit Candice Archie

In the 18th dynasty, Pharaoh Ahmose I reunited Egypt and restored its control over Nubia. He began military campaigns in Palestine, clashing with the Mitannians and the Hittites. His empire stretched from Nubia to the Euphrates River (“Iraq” today).

In addition to powerful kings such as Amenhotep I (1546-1526 BC), Thutmose I (1525-1512 BC), and Amenhotep III (1417-1379 BC), the New Kingdom was notable for Queen Hatshepsut (1503-1482 BC). She began ruling as a regent for her young stepson later to become Pharaoh Thutmose III, Egypt’s greatest military hero.

The controversial Pharaoh Amenhotep IV (1379-1362 BC) of the late 18th dynasty, disbanded the priesthoods dedicated to Amon-Re (a combination of the local Theban god Amon and the sun god Re). Amenhotep IV forced the exclusive worship of another sun-god, Aton, and renamed himself Akhenaton (“Servant of the Aton”). He also built a new capital in Middle Egypt called “Akhetaton”, known later as Amarna.

He angered the priesthood and Egyptian religious orthodoxy. Upon Akhenaton’s death, the capital returned to Thebes and Egyptians returned to worshiping a multitude of gods.

The 19th and 20th dynasties, ruled by the line of pharaohs named Ramses, saw the restoration of the weakened Egyptian empire and impressive temple and city buildings. According to biblical chronology, the exodus of Moses and the Israelites from Egypt occurred during the reign of Ramses II (1304-1237 BC).

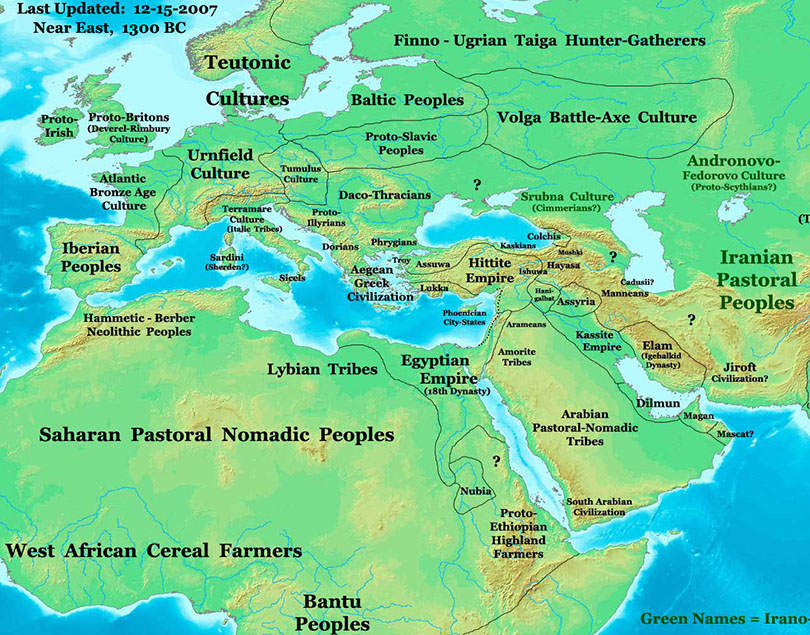

Ramses II Egyptian Empire around 1300 BC; credit Thomas A Lessman

The last “great” pharaoh from the New Kingdom was Ramesses III, who reigned three decades after the time of Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC). Though he won great battles vs. the Sea People, their presence in nearby Canaan may have contributed to new states such as Philistia after the collapse of the Egyptian Empire. Ramesses III was also compelled to fight invading Libyans in two major campaigns in Egypt’s Western Delta. The heavy cost of these battles slowly exhausted Egypt’s treasury and contributed to the gradual decline of the Egyptian Empire in Asia.

The severity of these difficulties is stressed by the fact that the first known strike in recorded history occurred during Year 29 of Ramesses III’s reign when the food rations dwindled. Something in the air prevented much sunlight from reaching the ground and also arrested global tree growth for almost two full decades until 1140 BC. One proposed cause is the Hekla 3 eruption in Iceland.

Following Ramesses III’s death, three of his sons would assume power as Ramesses IV, Ramesses VI, and Ramesses VIII, respectively. However, at this time Egypt was also increasingly beset by a series of droughts, below-normal flooding levels of the Nile, famine, civil unrest, and corruption. The power of the last pharaoh, Ramesses XI, grew so weak that in the south the Theban High Priests of Amun became the effective de facto rulers of Upper Egypt, while Smendes controlled Lower Egypt even before Ramesses XI’s death. Smendes would eventually found the 21st Dynasty at Tanis.

Third Intermediate Period

After the death of Ramesses XI, his successor Smendes ruled from the city of Tanis in the north, while the High Priests of Amun at Thebes ruled Southern Egypt while officially recognizing Smendes as king. Since both priests and pharaohs came from the same family, that was no big deal. Piankh assumed control of Upper Egypt, ruling from Thebes, with the northern limit of his control ending at Al-Hibah. The country was once again split into two parts with the priests in Thebes and the pharaohs at Tanis. Their reign seems without other distinction, and they were replaced without any apparent struggle by the Libyan kings of the 22nd Dynasty.

Shoshenq I, was a Meshwesh Libyan, who served as the commander of the armies and unified the country. He put control of the Amun clergy under his own son as the High Priest of Amun. There appear to have been many subversive groups, which led to the creation of the 23rd Dynasty running concurrently with the latter 22nd Dynasty around 945 BC. Oddly, this brought stability to the country for over a century. After the reign of Osorkon II the country had again splintered into two states with Shoshenq III of the 22nd Dynasty controlling Lower Egypt by 818 BC, while Takelot II and his son (the future Osorkon III) ruled Middle and Upper Egypt.

After the withdrawal of Egypt from Nubia at the end of the New Kingdom, a native dynasty took control of Nubia. Under king Piye, the Nubian founder of the 25th Dynasty, the Nubians pushed north in an effort to crush his Libyans ruling the Nile Delta. Piye gained control as far north as Memphis (a suburb of Cairo today). His opponent Tefnakhte submitted to him, but he was allowed to remain in power in Lower Egypt and founded the short-lived 24th Dynasty at Sais.

The Kushite kingdom to the south took full advantage of this division and political instability and defeated several native-Egyptian rulers such as Peftjauawybast, Osorkon IV of Tanis, and Tefnakht of Sais. Piye was succeeded first by his brother, Shabaka, and then by his two sons Shebitku and Taharqa. From 760 to 600 BC, five Kushite (Black) Pharaohs ruled all of Egypt from Nubia to the Mediterranean Sea. They constructed great buildings up and down the Nile and including pyramids, which they buried their kings under, rather than inside, like earlier pharaohs.

The power of the 25th Dynasty climaxed under Pharaoh Taharqa. The Nile Valley empire revived Egyptian arts and architecture. The Nubian pharaohs built or restored temples and monuments throughout the Nile valley, including Memphis, Karnak, Kawa, and Jebel Barkal. The Kushites developed their own Meroitic alphabet, which was influenced by Egyptian writing systems.

Taharqa initially defeated the Assyrians when war broke out in 674 BC. Yet, in 671 BC, the Assyrian King Esarhaddon started the Assyrian conquest of Egypt, took Memphis, and Taharqo retreated to the south, while his heir and other family members were taken to Assyria as prisoners.

The native Egyptian vassal rulers installed by King Esarhaddon as puppets were unable to retain full control, and Taharqa was able to regain temporary control of Memphis. Esarhaddon’s 669 BC campaign to once more eject Taharqa was abandoned when Esarhaddon died in Palestine on the way to Egypt.

Late Period

Taharqa’s successor, Tantamani sailed north from Napata, through Elephantine, and to Thebes with a large army to Thebes, where he was installed as the king of Egypt. From Thebes, Tantamani regained control of Egypt, as far north as Memphis. His troops were defeated by the Assyrians, who had a military presence in the Levant, then sent a large army southwards in 663 BC. Tantamani was routed, and the Assyrian army sacked Thebes to such an extent it never recovered. Tantamani was chased back to Nubia, but his control over Upper Egypt endured until 656 BC. At this date, a native Egyptian ruler, Psamtik I son of Necho, placed on the throne as a vassal of Ashurbanipal, took control of Thebes.

The last links between Kush and Upper Egypt were severed after hostilities with the Saite kings in the 590s BC.

Persian and Greek Dominance

Heliopolis, another important city and major religious center, was located in what are now the northeastern suburbs of Cairo. It was largely destroyed by the Persian invasions in 343 BC and partly abandoned by the late first century BC.

From the third century BC to the third century AD, northern Nubia would be invaded and annexed by Egypt. Ruled by the Macedonians (Persians) and Romans for the next 600 years, this territory would be known in the Greco-Roman world as Dodekaschoinos.

Kush was later taken back under control by the fourth Kushite king Yesebokheamani. The Kingdom of Kush persisted as a regional power until the fourth century AD when it disintegrated from internal rebellion amid worsening climatic conditions, and conquest by the Noba people.

Macedon (Greece) became a rising power in Europe, the Middle East, and Northern Africa. In 332 BC, Alexander III of Macedon (Alexander The Great) conquered Egypt with little resistance from the Persians. He was welcomed by the Egyptians as a deliverer. He visited Memphis and went on a pilgrimage to the oracle of Amun at the Siwa Oasis. The oracle declared him the son of Amun. He conciliated the Egyptians by the respect he showed for their religion, but he appointed Greeks to virtually all the senior posts in the country, and founded a new Greek city, Alexandria, to be the new capital.

Early in 331 BC, Alexander led his forces away to conquer Phoenicia and Babylon, never returning to Egypt.

Ptolemaic Dynasty Ended By Romans

Following Alexander’s death in 323 BC, a succession crisis erupted among his generals. Perdiccas ruled the empire as regent for Alexander’s half-brother Arrhidaeus, who became Philip III of Macedon, and Alexander’s infant son Alexander IV of Macedon. Perdiccas appointed Ptolemy, one of Alexander’s closest companions, to rule Egypt in the name of the joint kings. As Alexander’s empire disintegrated, Ptolemy soon established himself as the sole ruler of Egypt.

Ptolemy defended Egypt against an invasion by Perdiccas in 321 BC and consolidated his power during the Wars of the Diadochi (322–301 BC). In 305 BC, Ptolemy I took the title of Pharaoh and founded the Ptolemaic dynasty that was to rule Egypt for nearly 300 years.

The later Ptolemies took on Egyptian traditions by marrying their siblings, had themselves portrayed on public monuments in Egyptian style and dress, and participated in Egyptian religious life. Hellenistic culture thrived in Egypt well after the Muslim conquest. The Egyptians soon accepted the Ptolemies as the successors to the pharaohs of independent Egypt.

All the male rulers of the dynasty took the name, Ptolemy. Ptolemaic queens, some of whom were the sisters of their husbands, were usually called Cleopatra, Arsinoe or Berenice. The most famous member of the line was the last queen, Cleopatra VII, known for her role in the Roman political battles between Julius Caesar and Pompey, and later between Octavian and Mark Antony. Her apparent suicide at the conquest by Rome marked the end of the Ptolemaic Dynasty in 30 BC.

Rome ruled Egypt and most of the recorded world for several centuries.

The origins of modern Cairo traced to a series of settlements in the fourth century AD, as Memphis was continuing to decline. The Romans established a large fortress along the east bank of the Nile. The fortress, called Babylon, was built by the Roman Emperor Diocletian (285–305 AD) at the entrance of a canal connecting the Nile to the Red Sea that was created earlier by Roman Emperor Trajan (98–115 AD). Further north of the fortress, near the present-day district of al-Azbakiya, was a port and fortified outpost known as Tendunyas.

The Byzantine-Sassanian War between 602-628 AD caused great hardship and likely caused much of the urban population to leave for the countryside, leaving the settlement partly deserted. The site today remains at the nucleus of the Coptic Orthodox community. Cairo’s oldest extant churches, such as the Church of Saint Barbara and the Church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus are located inside the fortress walls in what is now known as Old Cairo or Coptic Cairo.

The Muslim conquest of Byzantine Egypt was from 639-642 AD. The city, known as Fustat served as a garrison town and as the new administrative capital of Egypt. One of the first projects of the new Muslim administration was to clear and re-open Trajan’s ancient canal in order to ship grain more directly from Egypt to Medina, the capital of the caliphate in Arabia. Ibn al-As also founded a city mosque at that time, now known as the Mosque of Amr Ibn al-As, the oldest mosque in Africa.

In 750 AD, following the overthrow of the Umayyad caliphate by the Abbasids, the new rulers created their own settlement to the northeast of Fustat which became the new provincial capital. This was known as al-Askar laid out like a military camp.

In 861 AD, a Nilometer was built on Roda Island near Fustat. Although it was repaired and given a new roof in later centuries, its basic structure is preserved, making it the oldest Islamic structure in Cairo.

In 878 AD, a commander of Turkic origin, Ahmad ibn Tulun, became effective governor of Egypt. He used his growing wealth to establish a new administrative capital to the northeast of Fustat. Between 876-879 AD, Ibn Tulun built a great mosque, now known as the Mosque of Ibn Tulun, at the center of the city, next to the palace.

In 905 AD, the Abbasids sent general Muhammad Sulayman al-Katib to re-assert direct control over the country. The al-Qatta’i was razed to the ground, except for the mosque which remains standing today.